Tucked in a cornfield near Nappanee, an old homestead whispers its stories to those who will listen.

Helen Mishler wanted to make sure those tales from the Daniel Stump Homestead would keep being heard, that those who came to visit would get a sense of the history of this place and those who lived here.

Helen died a few days before Christmas 2020, but because of her gift to the Community Foundation of Elkhart County, those stories will be heard for years to come.

Daniel and Salome “Sally” Stump moved to this plot of land from Canada in the late 1830s. They were seeking religious freedom and economic opportunity and settled in a place that had become Union Township in Elkhart County in 1837.

The family built the first buildings between 1838 and 1840, including a log cabin that included a kitchen and space for the 13 children to grow up.

Nearby is an Apple Butter House that provided space for weaving, butchering, shoeing horses, storing grain and more. Barns, an orchard and a cemetery all became part of the homestead. The family legend was that the apple trees on the property grew from seeds provided by Johnny Appleseed, according to Helen in a 2009 newspaper article.

The dominant tree on the property now is a large majestic one jutting up dozens of feet above the corn. The family planted a ginkgo tree soon after it arrived in the United States. It’s now likely one of the largest ginkgo biloba trees in the state, according to Chris Gillam.

Chris Gillam will assure that Helen Mishler’s wishes are carried out in regards to her estate.

The homestead stayed in the family, but the buildings were run down and needed attention by the time Helen and her sisters June and LaVonne Mishler Amo bought it in 1983 from their cousins who were some of the thousands of descendants of the Stumps.

No one had lived there since World War II, about the same time Helen had gone to work for CTS in Elkhart, where she was part of the effort to make items for the troops overseas. She lived nearby and attended Union Center Church of

the Brethren.

“It was really important to her that 100 years from now, these buildings still be here.”

— Chris Gillam

Advisor of Helen Mishler’s legacy fund

The buildings that were still standing were in rough shape. The small farmhouse, with original siding, roof and windows, has gotten some attention and has two communion benches inside that were part of the church down the road.

Using old photos, the Mishler sisters oversaw the construction of two barns using pieces from other historic barns in the area. The story of the pieces that were collected, of the 100-year-old trees that provided the siding, of the Amish craftsman who raised the barn in 1987 are all part of the lore that Helen loved telling and wants others to keep retelling.

The buildings on the homestead with their stories are characters in this story, but none of them are as important as Helen, Chris Gillam and attorney-now-judge Mike Christofeno.

Helen had grown up nearby and lived in the same house nearly all her life. She and her sister June never married, never had children.

Helen rented space on their farm to Chris Gillam, who brought cattle to her woods from May 1 to November 1 each year. If he was a day late in coming to load them, she called Chris. “She was particular,” Chris says. Even in the last decade of her life, she insisted on helping him load them onto the trailer. “They know me,” she told him.

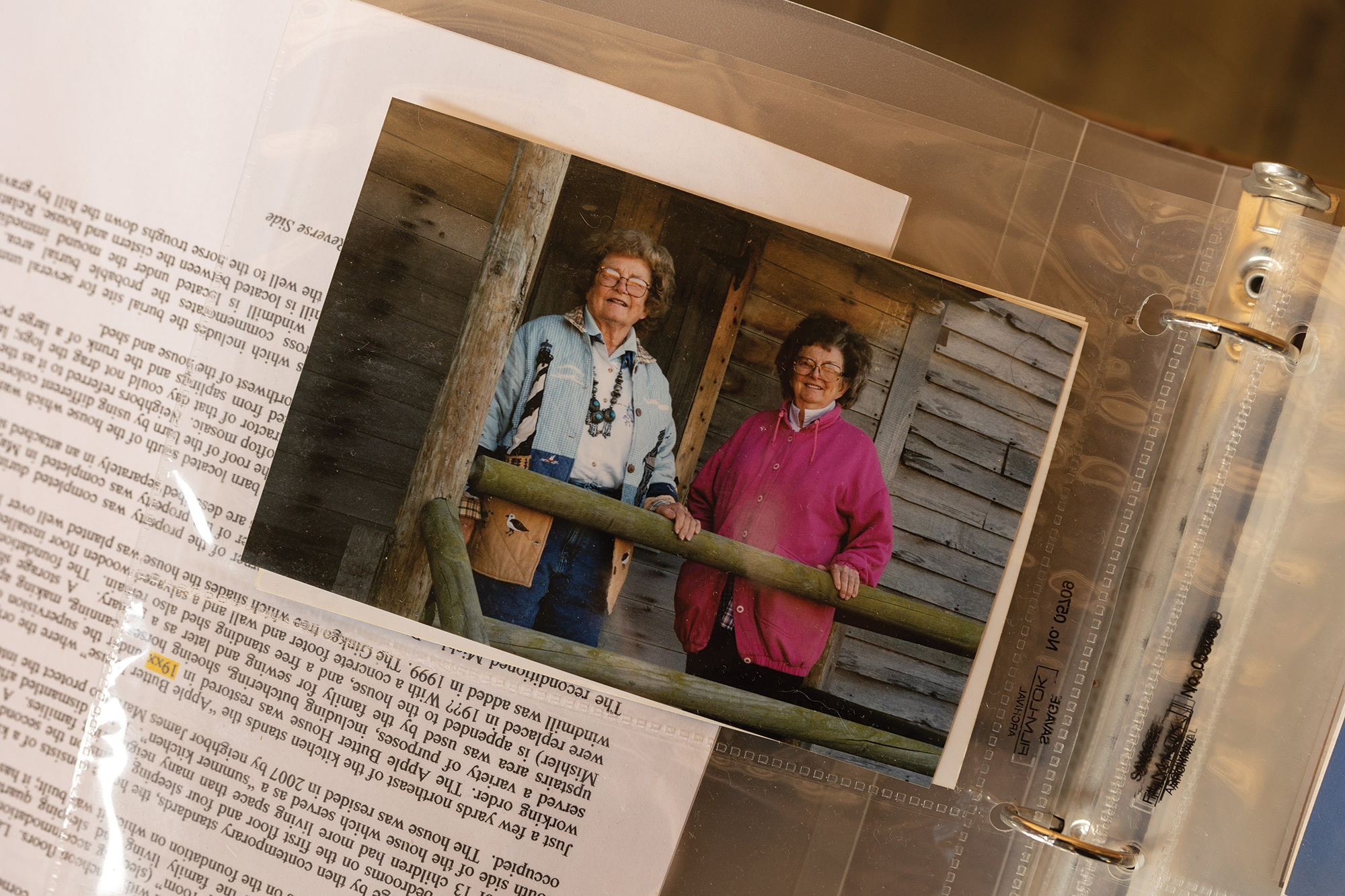

Helen Mishler and her sister June stand on the front porch of one of the buildings at the Stump homestead.

She maintained her property, picking up sticks and mowing her lawn. “You just do a little bit every day and you get the job done,” she told Chris.

Even a few years before her death, she rode a four-wheeler side-saddle — because she could no longer get her leg over the seat. She insisted on continuing to mow her lawn, though Chris would also come and help. “I would mow with her a lot. I’d call it mowing ballet,” he says.

She loved nature and worried about the critters. She nursed raccoons back to health and once told Chris that possums couldn’t help it if they are ugly.

She loved her family and history even more, but didn’t know how to pass on that legacy to others in the community. Her attorney, who was still in private practice, was Mike Christofeno. She had definite ideas about what she wanted. “Helen, like many of my elderly clients, knew what she wanted to do and had to make some decisions about how to do it,” Mike says.

They met at her home over refreshments. She drove to his office in Elkhart. They chatted not just about her will and legal affairs, but about their lives. Over time, they built trust and he presented options, including the Community Foundation, to help preserve her legacy.

She wanted control over how her family would be honored after her death. As they worked through the options, Helen saw the Community Foundation’s logo of a ginkgo leaf, which affirmed her choice to utilize what the foundation

could offer.

Her sisters had all passed away, as well as many of her friends. She didn’t understand why she was living so long and said, “My grave keeps calling me and wondering where I am.”

She couldn’t grasp how her frugal life of saving and sharing meant that she had big decisions to make about how to provide direction after her death. Chris and Mike walked alongside, helping Helen understand that by giving to the Community Foundation, it would remain there forever and could support both the homestead and others in the community.

Aerial view of the Mishler homestead

Though she declared, sometimes loudly and publicly, that Mike is “the best attorney in the world,” she had to turn to his son Jon after he became a judge. The first will that Mike drew up was witnessed by Dr. Robert Abel.

Jon Christofeno, with Carrie Berghoff and Jodi Spataro from the Community Foundation’s advancement team, set up a legacy fund.

Helen chose Chris to be her advisor on her legacy fund and to be the caretaker for the homestead. This means he is responsible for granting to nonprofits within the criteria she set. The purpose of the Mishler Brown Foundation is to honor Helen’s life by granting to nonprofits that support her interests of farming, agriculture, historic preservation of farms, barns and equipment.

After her peaceful death at home, some of her estate went to Union City Church of the Brethren and much of it to the Community Foundation. Her planning and work prior to her death meant that the homestead can become a place where people learn about the past and perhaps a way to live more simply in a world that is increasingly complicated. Though the homestead has never had running water or electricity, it has been used for reunions, weddings and other gatherings and Chris is looking at how to help others use it responsibly in the coming years.

“It was really important to her that 100 years from now, these buildings still be here,” says Chris. “She taught me to respect the past and make sure it’s passed on to future generations. She wanted us to know where we came from.”

The buildings on these five acres have tales to tell, lessons to teach.

This story appeared in the 2021 Annual Report.